Blog: Working reflexively to foster children’s safety in violence research

Associate Professor Tim Moore is the Deputy Director (Practice Solutions) at the Australian Centre for Child Protection at the University of South Australia.

After a decade of working directly with children, young people and families he moved into academia in 2005 to better understand children's lives and the best ways to support them and their families during periods of adversity. His research is underpinned by a commitment to promoting the needs, views and experiences of children and young people and supporting the development of practices, policies and programmes that respond to them. Over the past 13 years Tim has worked with children and young people on a range of participatory research projects across various topics including child sexual abuse.

In recent times, most discussions about children’s participation in research on many sensitive topics have moved from whether children should participate to how researchers can ensure that they can participate safely. Researchers and ethics committees have argued that with the right safeguards in place, children and young people can be involved in studies focusing on topics such as, among other things, health concerns, death in the family and radicalisation (Powell et al., 2020).

Given the sensitivities of violence research and the potential for participants experiencing harm, researchers engaging children and young people in such research must consider their ethical responsibilities and to balance children and young people’s rights to participation and to protection. This can be particularly pertinent for research on sexual violence against children where questions of disclosure, stigma, shame and blame can be fraught with challenges. One strategy that can provide violence researchers with the means to identify and respond to ethical challenges is ethical reflexivity. Reflexivity involves researchers taking a step back from the research process to critically consider what they are hoping to achieve, what is going on for participants and for themselves, and, in relation to ethics, to pre-empt, prevent or put in place safeguards to ensure the safety of participants (Moore, 2012). Moving beyond ‘reflection’, reflexivity requires the researcher to act: to make changes to their approach (Canosa, Graham, & Wilson, 2018). In violence research, ethical reflexivity requires the researcher to take action if risks are identified or other ethical challenges emerge.

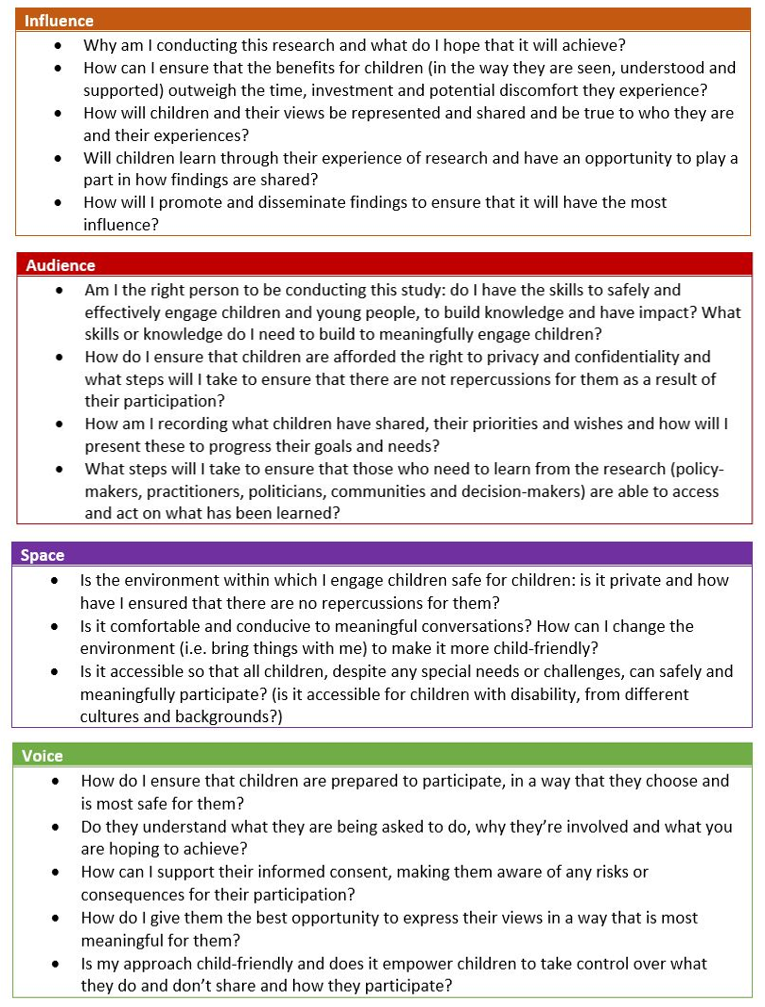

Reflexivity has been promoted in violence research (Åkerlund & Gottzén, 2017; Phelan & Kinsella, 2013), primarily in relation to identifying and responding to ethical challenges while research is being conducted. I would argue that reflexive practice should occur regularly: prior to, during and at the conclusion of research projects. Using Laura Lundy’s (2007) model of participation I’ve included some reflexive questions that might assist violence researchers consider ethical challenges and put in place strategies to manage them prior to engaging children and young people in research.

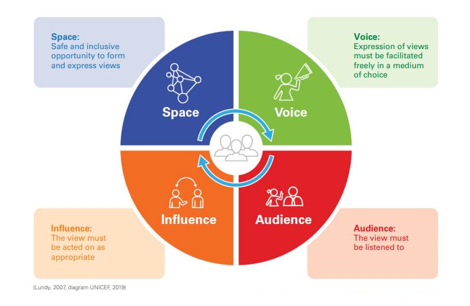

Lundy’s model[1] includes four key things to consider when engaging children and young people in participatory processes: “Space” (considers the context within which children and young people participate), “Voice” (considers what children and young people need to be able to safely form and express a view), “Audience” (considers who engages children and young people and who needs to hear and act on their views) and “Influence” (considers how children’s views are represented, how they have impact and how the use of the child’s input is fed back to children). Although Lundy and others usually begin by considering ‘space’ and ‘voice’, I have found thinking about influence and audience a useful place to start.

The following questions are not exhaustive but might be a good place to start. Researchers might spend some time considering their research, its nature, purpose and impact. Rather than just reflecting, researchers are encouraged to consider the ‘so what’? Asking ‘what might I do or do differently to ensure that their approach is ethical, child-friendly and responsive and enable young people to meaningfully engage throughout the life of the project.

Concluding reflections

While these questions are important to consider when working with all forms of violence, they are critical when thinking about engaging with children and young people who, through experiencing sexual violence, may struggle to find a sense of safety, feel empowered and trust others. We know that often young people report experiencing a ‘loss of control’ when dealing with services in the aftermath of abuse (Warrington, 2013). In addition, research shows that young people who have experienced sexual violence are often concerned about privacy and confidentiality (Barnert et al., 2020; Warrington, 2013; Pearce, 2010) and the potential for engagement in services and activities to heighten stigma and discrimination. ‘Ethical reflexivity’ is therefore a topic that warrants further exploration by the OVUN in the future in terms of its relevance and utility in research with children and young people affected by sexual violence.

References

Åkerlund, N., & Gottzén, L. (2017). Children’s voices in research with children exposed to intimate partner violence: A critical review. Nordic social work research, 7(1), 42-53.

Barnert, E., Kelly, M., Godoy, S., Abrams, L. & Bath, E. (2020). Behavioral health treatment “Buy-in” among adolescent females with histories of commercial sexual exploitation. Child Abuse and Neglect, 100 doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104042.

Canosa, A., Graham, A., & Wilson, E. (2018). Reflexivity and ethical mindfulness in participatory research with children: What does it really look like? Childhood, 25(3), 400-415.

Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’is not enough: conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. British educational research journal, 33(6), 927-942.

Moore, T. P. (2012). Keeping them in mind: A reflexive study that considers the practice of social research with children in Australia. ACU Research Bank,

Pearce, J. (2010). Children's participation in policy and practice to prevent child sexual abuse - Developing empowering interventions in Protecting children from sexual violence: A comprehensive approach. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, pp.75-85.

Phelan, S. K., & Kinsella, E. A. (2013). Picture this... safety, dignity, and voice—Ethical research with children: Practical considerations for the reflexive researcher. Qualitative inquiry, 19(2), 81-90.

Powell, M. A., Graham, A., McArthur, M., Moore, T., Chalmers, J., & Taplin, S. (2020). Children’s participation in research on sensitive topics: addressing concerns of decision-makers. Children's Geographies, 18(3), 325-338.

Warrington, C. (2013). ‘Helping me find my own way’: sexually exploited young people’s involvement in decision – making about their care, Professional Doctorate Thesis. Luton: University of Bedfordshire.