“We chose what was important to us”: Navigating the ‘messiness’ of participatory research with young people

Janelle Rabe is a doctoral researcher at Durham University-Department of Sociology and a member of the Centre for Research into Violence and Abuse (CRiVA). She has been part of the OVUN PhD Student Forum since 2022 - part of the Our Voices Programme at the University of Bedfordshire’s Safer Young Lives Research Centre. Her PhD, funded by the Northern Ireland and North East Doctoral Training Partnership (NINE DTP) and Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), is exploring the role of children and young people in preventing sexual violence using participatory research design. She has a decade of experience working with non-governmental organizations and policymakers in the Philippines on child rights and development issues. She has contributed to policy advocacy campaigns leading to the passage of laws on raising the age of sexual consent, child nutrition, and child protection.

Background

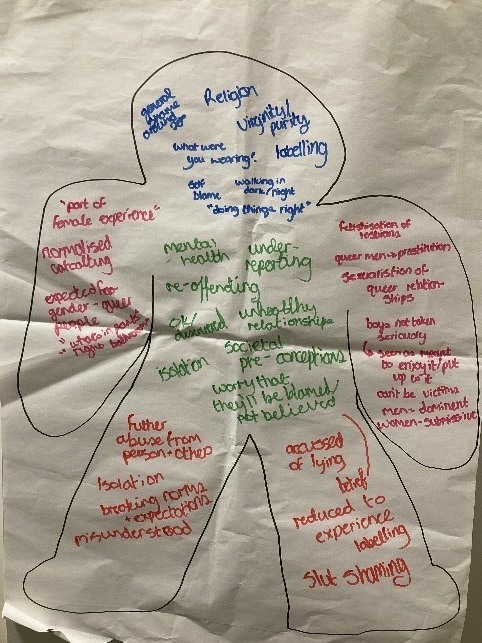

Young people have many brilliant ideas on addressing sexual violence. However, they usually do not have a lot of opportunities to share their insights and be listened to. This prompted my ongoing PhD study -- a participatory research project with 26 young people (13-18 years old) in North East England seeking to understand young people’s views on sexual violence and its prevention. With two groups of young people from a school and a youth club, we engaged in a series of 13 participatory workshops to explore this topic through a range of individual, paired, and group activities such as body maps, ranking and sorting, vignettes, and discussion groups. The young people involved are from the general population with no known experience of sexual violence. Still, it is recognised that young people might be exposed to everyday forms of sexual violence or indirectly affected as bystanders of sexual violence.

Valuing young people’s different forms of participation

My PhD commenced in October 2021 and from the beginning, I was eager to work with young people as advisory group members or co-researchers. This meant that we would decide together on different aspects of the research process such as developing the research methods, collaboratively doing the analysis and disseminating the findings.[1] However, after setting up an introductory recruitment workshop to explain the options of getting involved, both groups of young people did not seem to want formal researcher roles. They just wanted to join the workshops.

Initially, I was conflicted with the idea of designing the workshop activities instead of co-developing them with the young people. I was afraid it would make the research less participatory. I am tremendously blessed to have supportive supervisors who were able to allay some of my concerns about this. They told me about the importance of embedding both structure and flexibility in doing research with young people especially with a sensitive topic as sexual violence. They offered a helpful reminder of how pressurising it may be for young people to help co-design activities when they find it difficult to even talk about sex or sexual violence. There are also some practical considerations that might have influenced young people’s decision-making around this, such their schedules and other commitments in school and youth work. Whilst doing a fully participatory research project with young people is ideal, it is not always feasible. An important learning early on was therefore that young people may not necessarily want or be able to commit to being a co-researcher but there are other ways to promote their participation in the process and pursue a participatory ethos. It is important to respect the varied forms and levels of participation that young people are comfortable to commit to a project and that their contribution - whatever this may be - is valid and meaningful.[2]

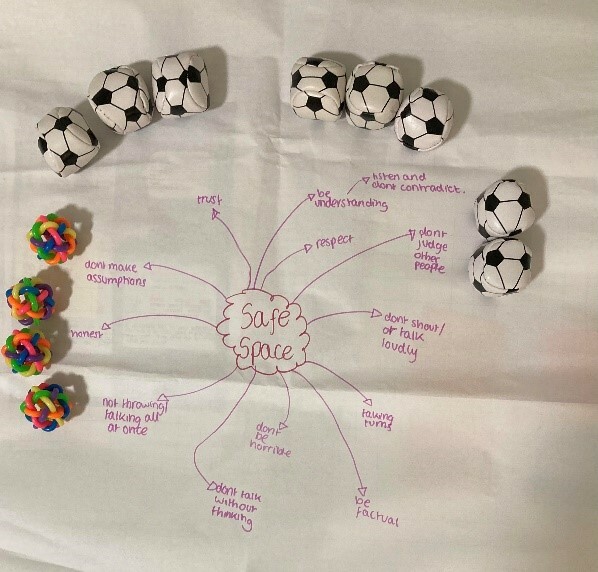

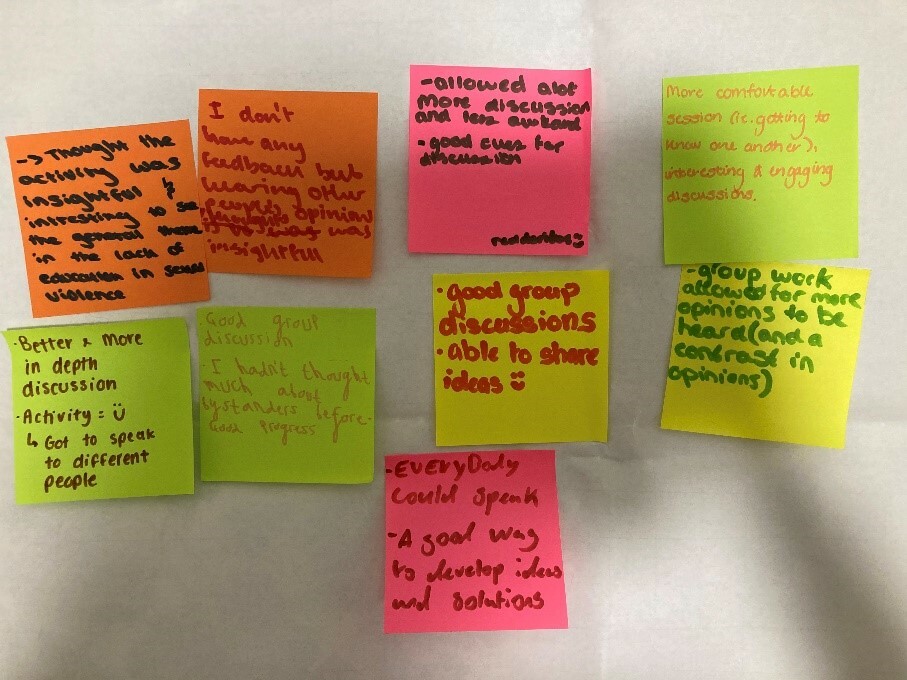

Participatory group work as an approach proved to be appealing to young people in sustaining their participation. The ‘Creating Safe Spaces’ toolkit by Camille Warrington[3] was a useful guide in planning and facilitating the workshops. For example, following the guide, the inclusion of icebreakers, the co-creation of a safe spaces group agreement at the start of workshops, and ensuring feedback mechanisms for young people throughout - were all essential components of the workshops.

Examples of young people’s feedback on group work are illustrated in the quotes below:

“Group work allowed for more opinions to be heard (and a contrast of opinions).”

“Enjoyed cooperative work/conversations.”

“We can all have input.”

Practicing flexibility and openness in the participatory research process

Opening the space for young people to decide on the topics of the workshops is a significant component in involving them in the co-production process. I did not want to impose my pre-determined ideas and instead, I wanted to follow their lead on the issues that mattered to them the most. Several young people appreciated the opportunity to decide on the topics as shown in their feedback below:

“I like how we all agreed on what we wanted to discuss.”

“We chose what was important to us.”

They led the project into exciting directions. One group focused on improving sex education around sexual violence and dealing with the shame associated with sexual violence. Meanwhile, the other group sought to understand better what sexual violence is and its impacts. While I was not initially expecting to delve into these specific topics, it became a joint learning experience for me and the young people.

Following their identified research agenda, I developed a flexible framework of activities for each workshop informed by our insights from previous workshops and research evidence. The openness of the workshop design provided spaces for young people to influence the direction of our conversations and the activities during the workshop itself. There were several instances when they wanted to do a different activity to what I had prepared. These instances demonstrated the ‘messiness’ of participatory research with young people when they might respond in ways that are different to what we expect.[4] Instead of seeing them as setbacks or frustrations, I appreciated them as crucial aspects of the co-production process and shared decision-making with young people.

Final reflections

Having conducted the 13 workshops, I am now at the stage of analysing the data. I will then conduct participatory analysis workshops to ensure that the findings and recommendations are young people-centred and align with their priority messages. Working with young people in this way has been an incredibly fulfilling learning experience. Together, the young people and I have co-produced an innovative methodology for doing participatory research and understanding sexual violence. This approach promotes shared understanding, safe spaces, mutual respect, and collaborative knowledge production. We also co-developed a proposed model to capture an expanded understanding of addressing sexual violence among young people, especially in schools. This entails improved access to sufficient information about sexual violence through relationships and sex education (Prevention), assurance of appropriate actions when sexual violence is reported or disclosed (Protection), and sustained support for the young person affected by sexual violence (Progression).

Young people’s feedback on the workshops illustrated that their participation was helpful to them and that the sessions served as safe spaces to express themselves. Some examples are seen below:

“I like it because it makes me feel acknowledged about the topic.”

"The sessions make me feel smart, educated, amazing, lush."

"Felt safe and understood."

It is incredibly important to talk and share learning about the messiness of doing this kind of research and the milestones along the research journey so we can learn from and support one another. The OVUN PhD student forum has been a valuable space for doing this. Joining the forum has been helpful for me to learn with and from other postgraduate researchers who are doing inspiring research projects. Our lively discussions contributed to enhancing my insights and understanding of the issue and methods involved in doing research on sexual violence. The group has been a very supportive, encouraging, and generous community which is even more vital due to the sensitive and emotion-heavy topics that many of us tackle. It is through spaces like these that we can develop more ways of working meaningfully with young people on addressing sexual violence.

References

Cahill, C. (2007) ‘Doing Research with Young People: Participatory Research and the Rituals of Collective Work’, Children’s Geographies, 5(3), pp. 297–312. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280701445895.

Grant, T. (2017) ‘Participatory Research with Children and Young People: Using Visual, Creative, Diagram, and Written Techniques’, in R. Evans and L. Holt (eds) Methodological Approaches. Singapore: Springer Singapore (2), pp. 261–284. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-020-9.

Moriña, A. (2021) ‘When people matter: The ethics of qualitative research in the health and social sciences’, Health & Social Care in the Community, 29(5), pp. 1559–1565. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13221.

Spiel, K. et al. (2020) ‘In the details: the micro-ethics of negotiations and in-situ judgements in participatory design with marginalised children’, CoDesign, 16(1), pp. 45–65. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2020.1722174.

Warrington, C. (2020) Creating a safe space Ideas for the development of participatory group work to address sexual violence with young people. Bedfordshire: University of Bedfordshire.

Email: anne.j.rabe@durham.ac.uk

Twitter: janelle_rabe

[1] Cahill, C. (2007) ‘Doing Research with Young People: Participatory Research and the Rituals of Collective Work’, Children’s Geographies, 5(3), pp. 297–312. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280701445895.

[2] Grant, T. (2017) ‘Participatory Research with Children and Young People: Using Visual, Creative, Diagram, and Written Techniques’, in R. Evans and L. Holt (eds) Methodological Approaches. Singapore: Springer Singapore (2), pp. 261–284. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-020-9.

[3] Warrington, C. (2020) Creating a safe space Ideas for the development of participatory group work to address sexual violence with young people. Bedfordshire: University of Bedfordshire.

[4] Spiel, K. et al. (2020) ‘In the details: the micro-ethics of negotiations and in-situ judgements in participatory design with marginalised children’, CoDesign, 16(1), pp. 45–65. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2020.1722174.